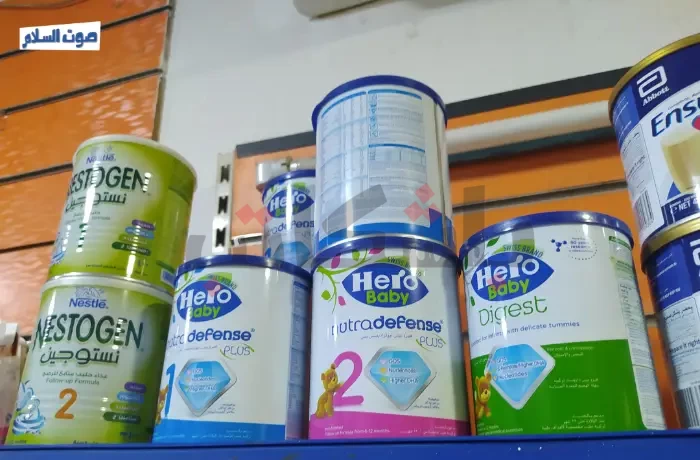

On nearly bare shelves, a scarce number of baby formula packages are lined up, poised to vanish swiftly from a pharmacy in the Dar Al-Salam neighborhood, southern Cairo. The heightened demand for baby formula amidst the crisis of unavailability, fueled by import issues and the dollar liquidity problem in Egypt, exacerbates this situation.

The pharmaceutical sector has been grappling with a series of crises, including a medicine shortage since early 2024, now extending to formula milk for newborns.

Mohamed Sherif, a pseudonym, a pharmacist in Dar Al-Salam, observes his limited stock of formula packages. He notes that the crisis began about a year ago, intensifying last May and July, leaving pharmacies with only one package per type. Medicinal formula for children with lactose intolerance and digestive issues has become unavailable, turning this essential commodity for newborns into an elusive dream.

For Ibtisam, a pseudonym, this dream remains out of reach, leaving her feeling helpless in the face of her child’s hunger. Despite having food at home, it is unsuitable for her five-months-old, who relies solely on formula milk. She continuously searches for the imported formula recommended by her doctor, noting that her child does not tolerate the subsidized milk provided by the health center.

Ibtisam expresses her wish that her child could rely on natural mother’s milk, but circumstances have forced her into a continuous search for formula, much like many other mothers in the same situation. “When I find a package, I buy it, and usually by the time it runs out, I manage to find another. However, I never have an extra package on hand in case it runs out unexpectedly. This constant fear that I won’t find a package in time and my son will go hungry is exhausting,” she explains.

Negotiations and Trickery

Ibtisam tried to navigate the challenging situation by negotiating with pharmacies, similar to other parents. She attempted to exchange the subsidized milk from the health unit for the appropriate type for her child. However, she struggled to find a willing pharmacy, and when she finally did, they did not have imported milk packages available.

These negotiations are not unusual, according to Sherif, a pharmacist, as some mothers resort to this due to the poor quality of subsidized milk provided by health centers. The demand for subsidized milk increases among families who cannot afford imported milk due to its high price, and the insufficiency of the monthly share they receive from the Ministry of Health, as children need about 7 or 8 packages per month, while their quota is only 4 packages.

As a result, families purchase the additional packages at a price of 100 EGP, equating to 25 EGP per package, while the official price at the health center is 5 EGP for formula milk from birth to six months, branded "Egy 1," produced by the local company "Egy Dairy," located in the industrial zone of the city of Tenth of Ramadan.

Packages for ages six months to two years are sold in pharmacies at 26 EGP, branded "Egy 2." After negotiation, the buyer pays the price difference to obtain the imported milk.

In a statement last April to the "Al-Hurra" website, Ali Auf, Head of the Pharmaceutical Division in the Chamber of Commerce, confirmed that the local market's annual consumption of baby milk amounts to about 50 million packages. Egypt imports half of this from abroad, while approximately 25 million packages are manufactured locally. This quantity is distributed entirely to Ministry of Health hospitals and health insurance facilities, and is available to citizens for 5 EGP per package, despite its actual cost reaching 150 EGP, according to Auf's statement.

Low Quality and Health Risks

Hajar Abdullah, a mother of two from Dar Al-Salam, continues to struggle with the scarcity of formula milk for children with lactose intolerance. Approximately five months ago, her infant daughter was diagnosed with an allergy, prompting the doctor to prescribe a specialized formula. However, as the crisis escalated, Hajar consulted the doctor again, who subsequently prescribed allergy drops to enable her child to consume the milk available at the health center.

Initially, Hajar felt worried, fearing she was risking her child's health. Meanwhile, in another area, Karima Ahmed, a pseudonym, was equally anxious after deciding to feed her daughter mashed food at just three months old, which is risky since children typically begin eating solid foods after eight months or a year.

However, Karima had no choice due to the scarcity of formula milk, compounded by being exploited during her search. A pharmacist sold her two packages of subsidized milk for 50 pounds.

Feeding her baby mashed food became her only option. Once the child adapted to this, Karima's anxiety eased, as she was no longer constrained by the formula milk shortage. She managed with the monthly share of subsidized milk, incorporating it into her child's daily meals, though not as the main source of nutrition.

The crisis for Karima and others persisted for a year, according to Abanoub Emad, a pharmacist. Pointing to the near-empty shelves, he remarked to “Sout Al-Salam”, "I am sure that in a day or two, these will be sold."

Abanoub expressed anger over the ongoing crisis, emphasizing the importance of formula milk as a fundamental food source for infants in their early months. "It is like basic commodities; it is unacceptable for it to vanish from the market like this," he commented.

Import Crisis

Abanoub explains that previously, he would receive one or more packages of the same type from companies’ representatives, resulting in a surplus at the pharmacy. Currently, however, he only receives one package from each representative, a situation echoed across most pharmacies. Consequently, there is no option but to use the milk from the health center, which he avoids due to its poor quality and the likely presence of sugar, harmful to children of this age.

Irene Saeed, a member of the Parliament and the Health Committee, confirms that the crisis has intensified since the beginning of the year. This escalation is linked to the medicine shortage and dollar liquidity crisis, which have impacted the import volume of non-Egyptian formula milk and some raw materials for the Egyptian dairy industry. However, in recent months - September and October - the medicine crisis began to ease, leading to the availability of a percentage of formula milk. Irene noted a decrease in milk-related complaints in November, indicating even a slight improvement in availability.

The crisis continues to strain the budgets of Karima, Ibtisam, Hajar, and others, who tirelessly search for just one package of milk to keep their children fed, even for a few days. The constant threat of running out of milk looms over them, compounded by the ongoing medicine shortage, which puts their children at risk of hunger.

Photography: Mariam Ashraf

- Stocks of infant formula displayed at some pharmacies

Medicine Shortage Crisis in Egypt